Change Data Capture (CDC) is a data integration technique that captures inserts, updates, and deletes from a source system and delivers them to downstream systems as an ordered stream of change events. Instead of re-copying full tables on a schedule, CDC propagates only committed changes so analytics, replication, and event-driven systems stay in sync with lower staleness.

CDC is most commonly implemented by reading database transaction logs (for example PostgreSQL WAL or MySQL binlog), although it can also be implemented with polling queries or triggers. This guide explains how CDC works, what CDC produces, delivery semantics, CDC methods, performance tradeoffs, recovery patterns, and how to evaluate CDC tools.

Key Takeaways

CDC moves committed change events (inserts, updates, deletes), not full tables on a schedule.

Reliable CDC depends on delivery semantics: ordering, retries, dedupe/idempotency, and delete handling.

Log-based CDC is usually best for low-latency, high-change systems; polling and triggers have clear tradeoffs.

Most “CDC is slow” issues come from destination apply and backpressure, not capture.

Production CDC requires snapshots, backfills, recovery, and schema-change policies to avoid rebuilds and silent drift.

Benefits of Change Data Capture

CDC is valuable because it changes the unit of data movement from "tables on a schedule" to "committed changes in order." That shift improves freshness, correctness, and operational stability in ways batch pipelines struggle to match as systems scale.

1) Lower freshness lag without batch spikes

Batch pipelines create unavoidable staleness windows and load spikes (every run pulls a lot of data at once). CDC distributes work continuously, so destinations stay closer to current state and the source avoids periodic extraction surges.

2) More correct replication of updates and deletes

Incremental batch approaches often miss deletes or approximate them with workarounds. CDC carries operation intent (insert, update, delete), which makes it easier to keep warehouses, search indexes, caches, and downstream services consistent.

3) Better recovery and rebuild options

CDC pipelines that track explicit positions can resume after failures without guessing. That reduces the frequency of "full reload" incidents and makes destination rebuilds and onboarding new consumers more controlled.

4) One change stream can feed multiple consumers

Once changes are captured as events, the same stream can power analytics, operational systems, and event-driven workflows without each team implementing its own extraction logic.

5) Scales better as data grows and changes accelerate

As tables grow, polling and batch windows tend to get longer and more fragile. CDC focuses on the delta, which is usually a better match for high-change systems where "only what changed" is the sensible unit of work.

6) Fewer brittle incremental loads

CDC reduces the need for “last updated timestamp” logic, incremental merge jobs, and full refresh fallbacks that commonly break as schemas and workloads evolve.

What CDC produces (change events, not just rows)

CDC does not copy “the table” over and over. It produces a change stream: a time-ordered sequence of facts about what changed in the source system. Downstream systems use those facts to reconstruct the same state (or a derived state) elsewhere.

In practical terms, a CDC stream usually contains four layers of information:

1) Identity: which record changed

Every CDC event must identify the entity that changed, typically via:

- Primary key columns (relational tables), or

- A document ID (document stores), or

- A composite key that the pipeline treats as the identity.

If the stream can’t reliably identify the record, you can’t do correct upserts/merges downstream—everything becomes “append and pray.”

2) Operation: what kind of change happened

At minimum, CDC events encode:

- Insert (new row/document)

- Update (existing row/document changed)

- Delete (row/document removed)

This matters because “update vs insert” changes how targets apply the event. A warehouse merge needs to know whether to upsert or delete. A cache invalidation path needs to know whether to evict.

3) State: what the new data is (and sometimes what it was before)

CDC is typically emitted in one of these shapes:

- After-only events (most common in analytics pipelines)

You get the new state of the row/document after the change. This is sufficient for maintaining a current-state replica.

- Before/after events (common for auditing and certain stream processors)

You get both the previous values and the new values. This makes it possible to answer questions like “what changed?” without looking up the prior record.

- Delta/partial updates (supported in some systems and configurations)

Only the changed fields are emitted. This can be more efficient, but it forces consumers to merge patches correctly and makes backfills harder unless you can reconstruct full state.

The key point: CDC streams are optimized to preserve change meaning, not just “a row dump.”

4) Position and time: where this change sits in the source history

A good CDC event carries metadata that allows a consumer to:

- Apply events in the right order

- Resume after failure without guessing

- Support dedupe and safe retries when consumers use the position correctly

Examples of “position” markers include:

- PostgreSQL log sequence / WAL position (often referenced as an LSN)

- MySQL binlog file + offset (and sometimes GTID)

- SQL Server LSN

- A monotonically increasing change version / token (in systems that expose them)

This is what lets consumers say: “I have safely processed up to position X,” which is the foundation of reliable recovery.

What “change events” enable that “rows” do not

Thinking in change events unlocks behaviors that simple replication doesn’t handle well:

- Deletes are first-class: you can propagate removals, not just additions.

- Replay is possible: you can rebuild targets by reprocessing a range of events (if retained).

- Auditing becomes feasible: before/after makes it possible to explain why a value changed.

- Multiple consumers can exist: analytics, search, caches, and services can all subscribe to the same truth source.

Common CDC output formats you’ll see in the wild

CDC tools may serialize events differently, but they nearly always boil down to the same semantic fields:

key: identifier of the recordop: operation (insert/update/delete)after: new representation (or null on delete)before: previous representation (optional)tsorsource_time: when the database committed the changepos: log position / ordering token (for recovery and dedupe)

If your CDC pipeline lacks either a stable key or a stable pos, you should assume you’ll eventually see duplicates, missed deletes, or corrupted replicas when failures happen.

How does Change Data Capture work?

Change Data Capture (CDC) works by turning database (or application) changes into an ordered stream of change events, then reliably applying those events to one or more downstream systems so they stay synchronized with the source.

At a systems level, CDC has three stages: detect → stream → apply.

Step 1: Detect changes in the source

CDC starts by identifying what changed in your source system. The detection mechanism depends on the CDC method and the technology you’re capturing from:

- Log-based CDC (most common at scale): the CDC connector reads the database’s transaction log (for example: PostgreSQL WAL, MySQL binlog, SQL Server log). It observes changes at commit-time, which is why it can preserve order and reliably capture inserts, updates, and deletes.

- Query-based CDC: a scheduled query repeatedly checks for rows that changed since the last run (usually requiring an

updated_attimestamp or version column). - Trigger-based CDC: triggers write changes into an audit table whenever inserts/updates/deletes occur.

For most production pipelines where correctness and low latency matter, log-based CDC is preferred because it avoids repeated table scans and captures the same sequence of changes the database uses for recovery.

Step 2: Convert changes into an ordered change stream

Once changes are detected, CDC converts them into events and publishes them as a stream your pipeline can process and transport. Each event includes record identity, operation type, and ordering metadata (covered in “What CDC produces”). That ordering metadata is what makes CDC operationally safe: it allows consumers to checkpoint progress (“processed up to X”) and resume correctly after restarts without guessing.

If your pipeline also does transformations (filtering fields, standardizing types, masking PII, computing derived fields), this is typically done on the stream before delivery, not by re-querying the source.

Step 3: Apply changes to targets (warehouse, lake, search, services)

Finally, the pipeline applies those CDC events to destinations so they reflect the latest source state. The apply strategy depends on the target:

- Warehouses / OLAP (Snowflake, BigQuery, Redshift, Databricks): events are applied using merge/upsert logic keyed on the primary key. Deletes must be mapped explicitly (hard delete or soft delete).

- Operational databases / indexes (Postgres, Elasticsearch, Redis, Firestore): events usually become upserts and deletes applied directly to the target system.

- Event streaming platforms (Kafka, Kinesis): CDC events are published as topics/streams for multiple consumers.

The hardest parts of “apply” are correctness under failure:

- Handling retries without corrupting state (idempotency / dedupe)

- Preserving ordering where it matters (especially for the same key)

- Ensuring deletes are represented consistently

What a CDC pipeline looks like end-to-end (example)

If a customer updates their address in PostgreSQL:

- PostgreSQL writes the update into WAL and commits the transaction.

- A CDC connector reads the WAL entry and emits an event like “customer_id=123 updated”.

- The pipeline publishes the event downstream (optionally transforming it).

- Snowflake (or another target) applies the event via a keyed merge so

customer_id=123now has the latest address.

Why this matters

CDC is powerful because it is not “copy data faster.” It’s “ship committed changes in order and apply them safely.” That’s what enables low-latency sync without constantly re-reading the source system—and it’s why strong CDC implementations invest heavily in ordering, checkpointing, recovery, and delete handling.

CDC delivery semantics

Most CDC guides stop at “read changes and ship them.” In production, the hard part is making sure those changes are applied correctly under retries, failures, and schema drift. That’s what delivery semantics are: the rules that determine whether your target ends up correct or just mostly up to date.

Ordering and transactional boundaries

Databases don’t change one row at a time in isolation. They commit transactions—often updating multiple rows across multiple tables. CDC needs to respect that reality.

What you want (and what you should verify your tool provides):

- Commit-order delivery: events are emitted in the same order the database commits transactions.

- Per-key ordering: changes to the same primary key are never applied out of order.

- Transaction grouping (ideal): events from one transaction are delivered as a unit (or at least labeled so consumers can avoid acting on partial state).

Why this matters:

- If events are applied out of order, targets can briefly—or permanently—show incorrect state (example: “status=SHIPPED” arrives before “order_created”).

- If a transaction is split and consumers react mid-transaction, downstream systems can trigger alerts, payments, or emails based on incomplete data.

Practical check: If you update two rows in one transaction, can your pipeline ever deliver only one of those changes before the other? If yes, document that behavior and ensure downstream consumers can tolerate it.

At-least-once vs exactly-once outcomes (duplicates + retries)

A lot of CDC systems are at-least-once in delivery: they guarantee you won’t miss events, but you may receive the same event more than once.

Duplicates happen during:

- Connector restarts after a crash

- Network timeouts where the producer can’t confirm the target commit

- Consumer retries after partial failures

- Rebalancing/partition movement in stream transports

What “exactly-once” usually means in practice is exactly-once outcomes: the target ends up correct even if delivery was at-least-once.

You get exactly-once outcomes with one of these patterns:

- Transactional apply: commit the destination write and the source checkpoint together (common in systems with tight integration).

- Idempotent writes: re-applying the same event produces the same final state (keyed upsert).

- Deduplication: drop repeats using a stable event identifier (log position / LSN / binlog offset / change token).

Rule for a “complete guide”: assume at-least-once delivery unless you can prove end-to-end exactly-once outcomes. Most pipelines fail not because they miss events, but because duplicates quietly poison aggregates or trigger double actions.

Deletes and tombstones

Deletes are the most common correctness gap in CDC implementations.

A CDC source can represent deletes in a few ways:

- Delete event: operation is

deleteand the “after” image is null. - Tombstone: a special marker that tells consumers “this key is now gone.”

- Soft delete (modeled): the source updates a column like

is_deleted=trueinstead of physically deleting.

What breaks pipelines:

- Targets that only support upserts but not deletes

- Consumers that treat missing data as “no change”

- Analytics models that assume “latest row wins” without delete semantics

You need a documented target strategy:

- Hard delete in the target (true replication)

- Soft delete in the target (keeps history, safer for analytics)

- Append-only history with a “current” view derived from events

If your CDC tool supports full refreshes but not deletes, you don’t have CDC—you have incremental loads with drift.

Idempotency and deduplication patterns (how to stay correct)

If you want CDC you can trust, define how consumers should behave when duplicates or out-of-order delivery occur (because they will).

Reliable patterns:

- Keyed upsert with last-write-wins

Apply event by primary key. If duplicates arrive, re-applying yields the same row.

- Apply only if the event is newer

Store a “last seen position” or “last updated time/version” per key and ignore older events.

- Use a stable event id for dedupe

Many logs expose a durable ordering token (log position). If a message repeats, drop it.

- Atomic merge at the destination

For warehouses, use MERGE keyed on primary key, and store a cursor/position so retries don’t reapply incorrectly.

- Quarantine on constraint errors

If an upsert fails due to type mismatch, missing columns, or constraint violations, route the event to an error stream instead of silently dropping it.

Practical sanity test: If you replay the last hour of events into an empty target, do you get the same final state as the source? If not, your semantics aren’t well-defined.

Methods of Change Data Capture

There are three primary ways to implement Change Data Capture (CDC). Each method answers the same question—“what changed?”—but they differ dramatically in latency, source impact, correctness (especially deletes), and operational complexity:

- Query-based CDC (polling tables for changes)

- Trigger-based CDC (writing changes into an audit/shadow table)

- Log-based CDC (reading database transaction logs such as PostgreSQL WAL or MySQL binlog)

If you’re choosing a method, compare them on five practical dimensions: latency, load on the source, delete handling, ordering guarantees, and recovery behavior.

Query-based Change Data Capture (polling)

Query-based CDC detects changes by running a recurring query, typically using an updated_at / time_updated column (or a monotonically increasing version) to fetch rows that changed since the last run.

Example table schema:

| id | firstname | lastname | address | time_updated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0001 | Joe | Shmoe | 123 Main St | 2023-02-03 15:32:11 |

Example query:

plaintext language-sqlSELECT *

FROM customers

WHERE time_updated > '2023-02-01 07:00:00';

What it’s best at

- Simple incremental loads where “near real-time” is not required

- Low-change tables where polling won’t compete with production traffic

- Situations where you only have read access and can’t access logs

Where it breaks down

- Deletes: hard deletes are invisible unless you implement soft deletes or maintain a separate delete log

- Latency: bounded by your polling interval (5 minutes means up to 5 minutes of staleness)

- Correctness under retries: “last_run_time” style logic can miss updates if clocks skew or timestamps aren’t reliably updated

- Source impact: polling large tables/indexes frequently can create contention, especially as data grows

Want a walkthrough? See our SQL CDC guide for more examples.

Trigger-based Change Data Capture (audit/shadow tables)

Trigger-based CDC uses database triggers to capture changes on INSERT, UPDATE, and DELETE, writing them into a shadow/audit table that downstream systems can read.

What it’s best at

- Capturing all operations including deletes without requiring log access

- Attaching extra metadata at write time (who/what changed it, application context)

- Smaller systems where write overhead is acceptable and tightly controlled

Where it breaks down

- Write amplification: triggers add extra writes on every change, which can materially affect high-throughput OLTP systems

- Operational complexity: managing triggers across many tables and schema changes becomes brittle over time

- Failure modes: if the trigger/audit mechanism fails or backlogs, it can create cascading write issues

Triggers are not “bad”—they’re just a tradeoff: they exchange simplicity of capture for ongoing performance and maintenance costs.

Log-based Change Data Capture (transaction logs)

Log-based CDC reads changes from the database’s transaction log (for example, PostgreSQL WAL, MySQL binlog, or SQL Server’s transaction log). Because these logs exist for durability and recovery, they contain the authoritative sequence of committed changes.

This approach is the most common choice for low-latency, high-throughput CDC because it:

- Captures inserts, updates, and deletes without polling tables

- Preserves commit order at the source, and can preserve correct apply order when the pipeline maintains ordering guarantees

- Typically adds less source contention than frequent queries because it’s not repeatedly scanning tables

Important nuance: log-based CDC usually has minimal additional load compared to polling, but it’s not “zero.” It still requires correct configuration, monitoring, and enough log retention to avoid falling behind.

Log-based CDC usually requires:

- A connector/agent that can read the logs (and appropriate permissions)

- A transport and apply mechanism (Kafka or a managed streaming layer, plus destination connectors)

- A recovery/checkpoint strategy so restarts don’t miss or double-apply changes

What it’s best at

- Near real-time replication into warehouses, lakes, and operational targets

- High-change workloads where polling would create unacceptable source load

- Systems where correctness depends on ordering and reliable recovery

Where it breaks down

- Permissions and access: reading logs often requires elevated privileges and careful security review

- Operational requirements: if consumers fall behind and logs roll over, you may need resnapshot/rebootstrap

- Schema changes: DDL and type changes can break consumers if not handled intentionally

For deeper reading: Gunnar Morling (Debezium) explains the advantages of log-based CDC vs polling in this post: Advantages of Log-Based Change Data Capture

If you need low latency and reliable deletes at scale, log-based CDC is usually the best fit. If your workload is small and freshness requirements are loose, query-based CDC can be “good enough” with far less setup.

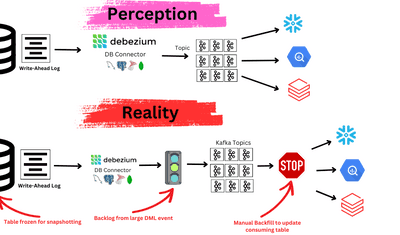

CDC latency and performance

CDC is “real-time” only if your pipeline can keep up end-to-end. The latency you experience is the time between a commit in the source and the change being queryable in the destination. In production, most “CDC is slow” complaints are not about capture—they’re about apply and backpressure.

Batch vs streaming CDC (why latency behaves differently)

Batch and streaming CDC differ less in whether data moves and more in how backlog accumulates.

- Batch extraction compresses change into scheduled jobs. Latency is bounded by the interval (hourly jobs can be an hour stale), and load arrives in spikes that often collide with peak database traffic.

- Streaming CDC turns changes into a continuous flow. Latency is driven by the slowest stage (capture, transform, or destination apply). When something slows down, the system accumulates lag rather than silently skipping data—so you can measure it and recover predictably.

The practical decision: if freshness is a product requirement (fraud signals, inventory, user-facing dashboards), batch creates unavoidable staleness windows. If freshness is “nice to have,” batch can be simpler—as long as you can tolerate the staleness and the spike load.

Where CDC latency actually comes from

End-to-end latency is usually the sum of three stages:

Capture latency (source → change stream)

How fast a connector can observe committed changes.

- Query-based CDC is bounded by the polling interval and indexing strategy. If you are polling, the implementation tradeoffs in SQL Change Data Capture are worth reviewing.

- Log-based CDC is typically faster and steadier, but it is still constrained by log configuration and the ability to continuously read without falling behind. Method choice matters most here: Log-based CDC vs Traditional ETL.

Processing latency (optional transforms)

Transforms can be cheap or can dominate latency, depending on workload.

- Simple projection, filtering, and type normalization are usually inexpensive.

- Enrichment, joins, heavy parsing, or write-amplifying transforms can turn a low-latency stream into micro-batched behavior under load. For practical framing, see Streaming ETL Processes CDC.

Apply latency (change stream → destination)

This is the most common bottleneck. Destinations impose real constraints: merge costs, index maintenance, API throttles, commit overhead, and concurrency limits. If the destination write path cannot apply changes as fast as they arrive, latency grows even if capture is instant. For an end-to-end view of these bottlenecks, see New Reference Architecture for CDC.

The only two metrics that reliably predict user pain

Throughput alone is a misleading signal. For CDC, two metrics correlate best with real-world staleness:

- Freshness lag (time-based): how old the newest applied record is in the destination.

- Backlog (work-based): how far the consumer is behind the source in processing the change stream.

Backlog growing steadily usually means the system is under-provisioned or throttled downstream. Backlog spiking typically points to bursts, large transactions, or destination slowdowns. For a correctness-first monitoring mindset, see CDC Done Correctly.

What “fast CDC” actually means in practice

A credible performance statement isn’t “milliseconds.” It’s an SLO that accounts for bursts and recovery:

- Target a steady-state freshness lag (example: p95 under 60 seconds for key tables).

- Define acceptable catch-up time after disruption (example: recover within 10 minutes after a connector restart without resnapshot).

- Maintain log retention headroom above worst-case downtime plus peak backlog.

Without headroom, pipelines often run fine until a burst or outage, then fall behind and require a rebootstrap.

Common performance failure modes and what they usually mean

- Lag increases gradually over days: destination apply is under-provisioned or constrained by merge/index costs.

- Lag spikes at specific times: large transactions, batch writes, or downstream throttling cause bursty backpressure.

- Frequent resyncs or “full refresh” behaviors: insufficient retention headroom or weak recovery strategy. This is a common reason teams choose managed CDC instead of owning the operational burden: Why Buy Change Data Capture.

Reader takeaway

If the goal is low-latency CDC that stays low-latency, optimize in this order:

- destination apply capacity and merge strategy,

- transform cost on the hot path,

- capture tuning and retention headroom.

For broader selection criteria and tradeoffs, see the CDC Comparison Guide.

Snapshots, backfills, and recovery

Most “CDC pipelines” are not CDC-only. In production, CDC is usually a two-phase system: you load an initial baseline, then keep it current by continuously applying changes. The baseline and the recovery story determine whether the pipeline stays reliable after outages, destination rebuilds, or new consumers.

Initial snapshot vs ongoing CDC

A CDC pipeline typically begins with an initial snapshot (sometimes called an initial load) so the destination has a complete starting state. After the snapshot, the pipeline switches to continuous change streaming.

The operational risk is the handoff between these phases. If rows change while the snapshot is running, a naive design can:

- miss changes (if streaming starts after the snapshot without a coordinated start position), or

- double-apply changes (if both snapshot and stream deliver overlapping updates without idempotent apply).

A durable CDC architecture coordinates snapshot + streaming around an explicit checkpoint/position so the pipeline can prove which changes are included and which are still pending. This “handoff correctness” is exactly what the end-to-end design in New Reference Architecture for CDC focuses on.

Backfills are normal operations, not edge cases

Backfills are not a sign something went wrong. They are routine lifecycle operations you will do repeatedly as systems evolve. Common triggers include:

- Adding a new destination (e.g., a new warehouse, lake, search index, or cache)

- Adding a new table/collection to an existing pipeline

- Fixing a mapping or transformation bug and needing to recompute history

- Rebuilding a destination after data loss or schema/model changes

- Recovering after extended lag when the source no longer retains enough history to replay cleanly

A CDC system that treats backfill as “start over from scratch” turns everyday changes into multi-hour incidents. A key principle in production-grade CDC is to make backfill predictable and controlled, which is a major theme in CDC Done Correctly.

Three backfill strategies (and when to use each)

There isn’t one “best” backfill method. The right choice depends on how much history you need, whether you can replay changes, and how expensive it is to reload state.

Full re-snapshot (simple, expensive)

Reload the current state of the dataset and rebuild the destination from scratch.

Use when: the destination is corrupted, the schema/model changed significantly, or you cannot trust historical change replay.

Time-bounded backfill (fast, requires retention/headroom)

Replay changes from a known safe point (for example, “replay the last 6 hours”) and reconcile.

Use when: a destination outage or apply slowdown created a gap, but the source/stream still retains enough history to replay reliably.

Selective backfill (surgical, requires strong keys and partitioning)

Reload only a subset (a table, tenant, shard, partition, or key range) instead of the full dataset.

Use when: only one domain is impacted (e.g., “customers” is wrong but “orders” is fine), or when onboarding a consumer that only needs a slice of history.

This is also the practical difference between CDC that is “fast when everything is healthy” and CDC that stays usable under real operational churn. If you want a deeper framework on the tradeoff between owning these recovery mechanics versus buying them, see Why Buy Change Data Capture.

Falling behind: the retention cliff most teams discover too late

CDC depends on retained history in some form: transaction logs, change feeds, or durable event storage. If the consumer falls behind far enough that the source can no longer provide the required history, you hit a retention cliff: the pipeline cannot safely continue from its last checkpoint and must rebootstrap via snapshot.

Symptoms practitioners recognize:

- lag increases steadily and never returns to baseline

- restarts “work” but the system remains permanently behind

- after a long outage (weekend/holiday), the pipeline requires reinitialization

This is why CDC at scale is as much a replication and recovery problem as it is an ingestion problem. If you want to reinforce that CDC behaves like replication with operational constraints, link here: CDC Replication.

Recovery: what “good” looks like after a failure

A production-grade CDC pipeline should support these recovery behaviors without manual heroics:

- Resume from last committed checkpoint

Restart without missing events and without reprocessing large windows unnecessarily.

- Replay a bounded window safely

If a destination was down, replay a defined range and reconcile without corrupting state.

- Rebuild destinations without touching the source application

If a warehouse table is dropped or an index is rebuilt, the pipeline can backfill and continue.

- Validate correctness after recovery

Recovery isn’t complete until validation brings confidence back: freshness lag returns to normal, key cardinality matches expectations, and critical aggregates do not drift.

Backfill and recovery are easier to implement (and easier to trust) when the pipeline is designed around explicit checkpoints, bounded replay, and destination rebuilds. For an end-to-end blueprint of how those pieces fit together, see New Reference Architecture for CDC. For the correctness and reliability principles that prevent silent drift during retries and replays, see CDC Done Correctly.

CDC is not just “stream changes.” It’s snapshot + streaming + backfill + recovery. If the system can’t backfill predictably and recover cleanly, it will eventually require disruptive rebuilds—usually at the worst possible time.

Schema changes and CDC

Schema changes are one of the fastest ways to break an otherwise healthy CDC pipeline—often without obvious errors. The risk isn’t just “pipeline failure.” It’s silent corruption, where data keeps flowing but downstream consumers interpret it incorrectly.

Safe changes (usually low risk)

These changes are typically compatible with CDC if your destination and transforms can tolerate new fields:

- Add a nullable column (or a column with a default)

- Add a new table to the pipeline

- Add non-breaking fields to JSON documents

Even “safe” changes can become risky if downstream models assume a fixed schema (common in brittle transforms).

Breaking changes (high risk)

These changes frequently require a coordinated migration plan:

- Primary key changes (including composite key changes)

CDC apply logic depends on stable keys. Change the key and you can’t reliably upsert/merge.

- Type changes (int → string, timestamp precision changes, enum changes)

These often break destination constraints or produce wrong aggregations.

- Renames and splits/merges (column renamed, table split into two, etc.)

CDC connectors may emit new fields, but consumers may treat them as missing or new semantics.

If you want a deeper explanation of why schema evolution is often the limiting factor for reliable CDC, see CDC Done Correctly.

DDL and “schema drift”: decide what your pipeline guarantees

CDC tools vary in how they handle DDL (schema change operations). Regardless of tooling, your pipeline should define one of these policies:

- Ignore schema changes and require manual updates (simpler, higher operational burden)

- Allow additive changes automatically but block/alert on breaking changes (most practical)

- Version schemas explicitly and route incompatible events to a quarantine stream (most robust)

Practical checklist (copy/paste into your runbook)

- Confirm the primary key is stable and matches destination merge keys

- Treat type changes as migrations, not “minor edits”

- Decide how to handle renames (map old → new or migrate consumers)

- Add alerts for apply errors and schema mismatch (don’t allow silent drops)

- When in doubt, backfill affected tables to re-establish a clean baseline (see CDC Replication)

When should you use CDC?

Use CDC when the business outcome depends on freshness, correct replication of updates and deletes, or continuous downstream processing—and when batch jobs become fragile as volume grows.

Use CDC for real-time or near real-time analytics

If dashboards, anomaly detection, or operational reporting require current data, CDC is the most direct path to keep analytics systems synchronized without repeatedly re-reading large tables. For an end-to-end blueprint of how CDC fits into a modern analytics stack, see New Reference Architecture for CDC.

Use CDC for replication and system synchronization

CDC is a strong fit when you need to keep a secondary database, cache, search index, or service in sync with a source of truth—especially when updates and deletes must propagate correctly. This is the core replication use case: CDC Replication.

Use CDC for streaming ETL and event-driven applications

If downstream systems need to react to changes (fraud signals, inventory updates, workflow triggers), CDC provides a reliable change stream you can transform and route in motion. A practical framing of CDC as a streaming ETL input is here: Streaming ETL Processes CDC.

Use CDC when batch ETL becomes operationally expensive

If you’re constantly tuning schedules, fighting long batch windows, or rebuilding broken incremental loads, CDC can reduce operational churn—especially when implemented as log-based CDC rather than polling. For a clear comparison of CDC vs traditional extraction patterns, see Log-based CDC vs Traditional ETL.

CDC tools and platforms

Choosing a CDC tool isn’t about “does it support Postgres.” Most tools do. The real differentiators are delivery semantics, backfill and recovery behavior, schema-change handling, and how much infrastructure you’re willing to operate.

What to compare (decision criteria that actually matter)

Use this checklist to avoid selecting a tool that works in a demo but fails under retries, bursts, and schema changes:

- Capture method

- True log-based CDC vs polling / “incremental sync”

- Source support (Postgres WAL, MySQL binlog, SQL Server log, Oracle redo, MongoDB oplog/change streams)

- Delivery semantics and correctness

- How duplicates are handled under retries (idempotency / dedupe)

- Ordering guarantees (at least per-key ordering)

- Delete handling (hard deletes, soft delete options, tombstones)

- Backfill and recovery

- Initial snapshot + streaming handoff correctness

- Adding new destinations with backfill (without disrupting existing pipelines)

- Bounded replay vs “full resync” as the default recovery response

- Schema change behavior

- Additive evolution support

- What happens on breaking changes (pause, error stream, silent drop, auto-cast)

- Operational burden

- Whether you must run Kafka / Connect infrastructure

- Monitoring and lag visibility

- Failure handling (dead-letter/quarantine behavior)

- Cost profile as volumes and destinations scale

How to choose (fast decision rules)

- If you need sub-minute freshness and reliable propagation of updates and deletes, prioritize log-based CDC with clear retry and dedupe semantics.

- If you expect to add destinations over time, prioritize systems that support repeatable backfills and bounded replay instead of frequent full resyncs.

- If your destination is a warehouse, validate the apply strategy (merge/upsert behavior, delete handling, batching) because destination apply is often the real bottleneck.

- If your schemas evolve frequently, choose a tool with explicit behavior for breaking changes (pause + alert or quarantine), not silent drops.

Where to go deeper

- Compare approaches (managed vs open source vs hybrid): CDC Comparison Guide

- See popular tools and tradeoffs: Best Change Data Capture Tools

- Solution overview (high-level): Change Data Capture

Database-specific deep dives

- MySQL: Complete CDC Guide for MySQL

- PostgreSQL: Complete CDC Guide for PostgreSQL

- SQL Server: Guide: Change Data Capture in SQL Server

- Oracle: Oracle CDC

- MongoDB performance considerations: MongoDB Capture Optimization

This version is tighter, avoids repetition, and doesn’t make any competitor-specific claims you’d need to defend.

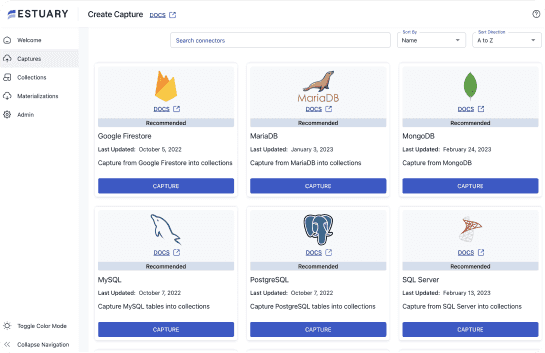

Why consider Estuary for CDC?

Estuary is built around the idea that CDC should be reusable, recoverable, and correct under retries—not just “fast.” In Estuary, CDC isn’t a one-off connector job. Captures ingest changes into collections, which act as the durable streaming data layer for downstream materializations. Materializations then apply those changes into one or more destinations with backpressure-aware batching.

CDC capabilities that matter in production

- Log-based + incremental snapshot behavior (where supported): captures run continuously and ingest changes into collections, which can then be reused for replay/backfill and additional downstream consumers without re-extracting from the source.

- End-to-end correctness options: when the destination supports transactions, Estuary integrates its internal transactions with the endpoint to provide end-to-end exactly-once semantics; for non-transactional targets, semantics are necessarily weaker (at-least-once) and must be handled via idempotency/dedupe patterns.

- Backpressure-aware application to destinations: materializations are sensitive to endpoint backpressure and can adaptively batch/combine updates as the destination slows (important for warehouses and “busy DB” targets).

- Operational backfills (not a rebuild-only story): Estuary supports incremental backfills on captures to refresh collections from the source without dropping destination tables, and then re-materializes as part of normal processing.

- Schema evolution support: evolutions help prevent mismatched specs across a flow by updating affected bindings and triggering backfills where needed (for example, recreating a destination table and backfilling).

- Time travel controls for materializations: you can restrict what gets materialized using

notBefore/notAftertime boundaries—useful for scoped replays, controlled cutovers, or limiting historical ranges.

If your CDC requirements include multiple destinations, repeatable backfills, and clear semantics under retries, these platform-level behaviors tend to matter more than connector checklists.

Conclusion

Change Data Capture is a practical way to keep systems synchronized by shipping committed changes—inserts, updates, and deletes—instead of re-copying full datasets on a schedule. When implemented correctly, CDC reduces staleness, improves replication reliability, and enables streaming ETL patterns that batch jobs struggle to support.

The difference between “CDC that runs” and “CDC you can trust” comes down to semantics and recovery: ordering, duplicates, deletes, schema changes, and the ability to backfill without constant rebuilds. If you want a blueprint for building CDC that survives real operational conditions, start with New Reference Architecture for CDC and the reliability principles in CDC Done Correctly. For tool selection and tradeoffs, see the CDC Comparison Guide and Best Change Data Capture Tools.

FAQs

Is CDC the same as replication?

What is the best CDC method?

Do I need Kafka for CDC?

About the author

With over 15 years in data engineering, a seasoned expert in driving growth for early-stage data companies, focusing on strategies that attract customers and users. Extensive writing provides insights to help companies scale efficiently and effectively in an evolving data landscape.